The gut microbiome and gut dysbiosis are buzz words right now, but it’s for a good reason. As conventional medicine continues to play catch up with what East Asian Medicine practitioners have known for centuries, the gut microbiome is SO important. Many of my patients have heard me talk about gut dysbiosis and how it can be a major player in their overall health. And if you look back at an earlier blog post about nitric oxide, you can start to connect the dots on how crucial it becomes that we pay close attention to what we eat on a daily basis, because it can literally make us sick over time.

The bacteria that colonize the human GI tract are far from passive bystanders in the balance of health and disease. Extensive research over the past 20 years has served to clarify the relationships between healthy bacteria populations and conditions as diverse as atherosclerosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), autoimmunity, autism, ADHD, and certain cancers.

Recent advances in microbiology and nutritional biochemistry continue to reinforce the ancient wisdom maintained by Hippocrates nearly 2500 years prior, “All disease begins in the gut”. In hindsight, it can be difficult to assume otherwise considering that 70 – 80% of immune tissue is situated in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Still, more recent data has served to explain many of the processes by which GI imbalances can lead to immune dysfunction and subsequent life-threatening conditions like cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer, autoimmune disease, vision loss and neurologic decline.

While much of the 21st century has focused on the genetic and epigenetic aspects of disease, multi-institutional research initiatives like the Human Microbiome Project have served to highlight the fundamental importance of bacteria species that colonize the human GI tract. The human microbiome is the collection of all microorganisms living in association with the human body, though the highest concentrations of bacterial organisms are known to reside in the colon.

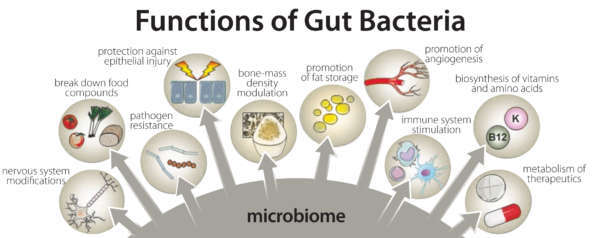

Amazingly, the bacteria that comprise the microbiome outnumber human cells in a 10-to-1 ratio and express roughly 1000 more genes than identified in human DNA. The successful symbiotic relationship involving human host and commensal gut bacteria cannot be overstated considering the benefits they provide: defending against pathogenic microbes, aiding in digestion, synthesis of vitamins (e.g., K, B12, folate), liberating short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) for energy, production of neurotransmitters, protecting intestinal barrier structure and function, and regulating immune activity to respond appropriately to harmful and non-harmful matter.

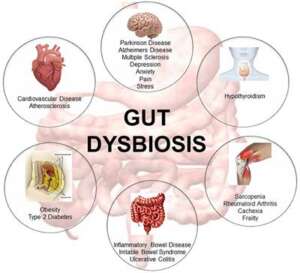

Dysbiosis is characterized by the qualitative and quantitative changes in intestinal bacteria, their metabolic activities, or local distribution that produces harmful effects on the host. Considering the critical functions of these bacteria, returning to a state of health may not be possible without first correcting any significant bacteria imbalances.

Dysbiosis can lead to systemic inflammatory conditions and diverse disease states by way of multiple pathological processes, like increased intestinal permeability (“Leaky Gut”) for example. Dysbiosis is largely characterized by reductions in beneficial (gram-positive) bacteria, which no longer engage in the essential metabolic and protective activities that maintain healthy GI function.

Additionally, the increased presence of harmful bacteria creates a toxic burden that promotes further inflammation and can stimulate pathological processes in more distant tissues and organs including the liver, brain, kidneys and joints. Correcting dysbiosis is a fundamental consideration for addressing conditions characterized by chronic pain and fatigue, irritable and inflammatory bowel disorders, mood and neurological dysfunction and multiple forms of autoimmunity.

Gut microbiome dysbiosis has been associated with inflammatory diseases. The human inflammatory response leads to an overproduction of nitric oxide (NO) in the gut. However, so far, the influence of NO on the human gut microbiota has not been characterized. A study using in vitro fermentation systems with human fecal samples to understand the effect of NO on the microbiome was performed and it showed that NO modified the microbial composition and its functionality. High NO concentration depleted the microbiome of beneficial butyrate-producing species and favored potentially dangerous species (E. coli, E. faecalis, and P. mirabilis), which can sustain high NO concentrations. This work shows that NO may participate in the vicious circle of inflammation, leading to detrimental and irreversible consequences on human health.

This demonstrates why gut health is a key component to overall health and well being. It also gives you some insight into why this is something that is heavily focused on in my office. If your gut isn’t happy, you’re body and mind aren’t happy. It’s a big deal. If you want to find out more, give us a call or set up an appointment online today.